Transcription: On Sleep

We spend around a third of our life asleep, yet we know very little about what goes on while we lay blissfully unconscious.

Hello, and welcome to Transcription, a weekly overview of research happenings in biotechnology and immunology! Subscribe to stay informed and support my work:

This one is coming out a week late — sorry. I was traveling for a wedding (congratulations Will and Kerry!) and the sleep disruption knocked me off schedule. Funny enough, there were a few interesting papers on sleep recently. So let’s dive into what they found.

How good is sleep?

It’s the best! Sleep lets us recover from our prior day. Our heart rate lowers tremendously and our brain activity decreases, allowing our body to use this newfound energy to build muscle, reconnect neurons, and heal injuries.

Sleeping throughout the animal kingdom is built on the day-night cycle known as the circadian rhythm. This rhythmic signaling is found throughout many species, such as fruit flies, trees, and bacteria. Even nocturnal (such as owls) and subsurface animals (like blind mole rats) maintain the 24-hour circadian clock cycles. Indeed people in experiments that are isolated from the natural day-night cycle continue to maintain an approximate 24-hour rhythm of sleep patterns. In 2017, the Nobel Prize in Medicine went to scientists who uncovered the genes that control the circadian rhythm in our cells.

We have studied and continue to study how we are able to sleep. But why we sleep is more elusive.

We spend around a third of our life asleep, yet we know so little about what goes on while we lay blissfully unconscious. It’s a challenging thing to study! We cannot chemically induce sleep via anesthesia because that is a different state than our natural sleep cycle. It disrupts the circadian rhythm. So any research participants should be going through their usual nightly routine. And the researchers try not to disturb this cycle or the patient’s once asleep, which limits the information that can be collected.

But the positive effects of sleep cannot be disputed. Getting 8 hours of sleep every night is associated with better injury recovery, more robust memory generation, lower risk of neurodegenerative disease, and healthier metabolism. Chronic sleep deprivation, on the other hand, impairs brain development, increases blood pressure, and heightens the risk of developing obesity, stroke, diabetes, and kidney disease. Even a 5-hour change in sleep cycle, for instance as a result of travel from the eastern US to Europe for a wedding, temporarily disrupts metabolism.

Sleep is important, and we want to know why.

And the little we do know has just expanded. A series of papers published over the last week has deepened our understanding of what happens while we rest.

One of the most well established benefits of sleeping is long-term memory generation. The leading theory is that while asleep, the brain goes through things that occurred over the previous day and prioritizes what to keep and what to toss. Notable memories are sent for long-term storage, while unimportant ones are forgotten.

How this prioritization happens, and how the brain then stores a memory, was unknown. Until now.

Memories are held in the connections between individual neurons. These connections are known as synapses. One of the hallmarks of learning and brain development is “synaptic plasticity”: the ability for our neurons to reconnect with new neurons when novel information is presented to them.

Neurons communicate with one another via these synapses by transmitting electrical pulses. And as a result, we can measure these communications via electrodes that detect particular electrical patterns. If these electrical patterns are more frequent, there is more neuron activity in the brain. If they’re less frequent, brain activity is lower.

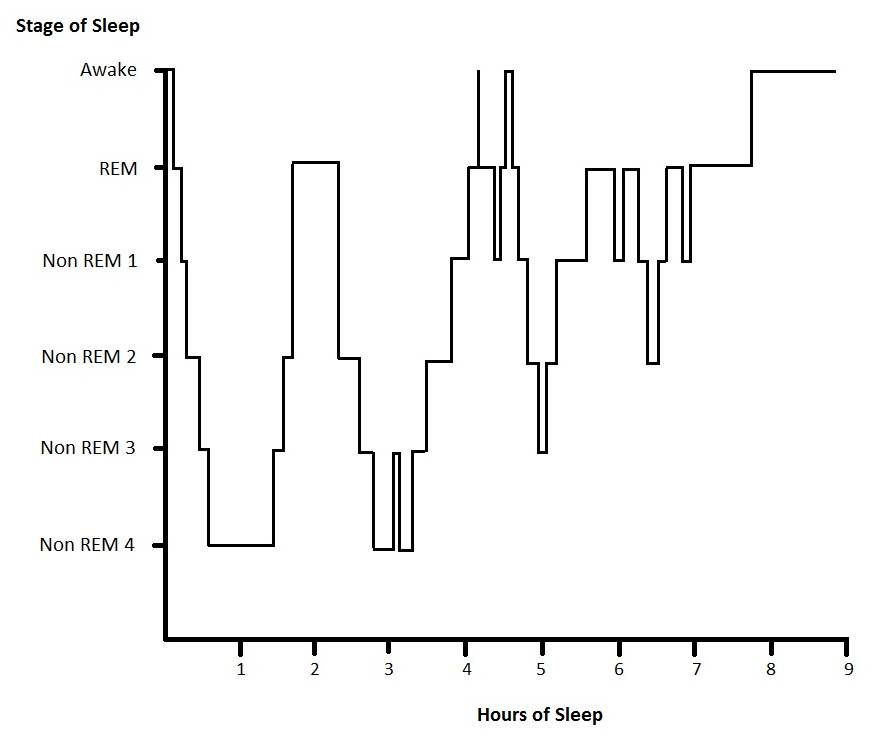

When we sleep, our brain activity decreases, but it does not stop altogether. And as a result of measuring these electrical patterns we know there are distinct stages of sleep. For instance during deep sleep, brain activity is very low and electrical pulses are infrequent. These are known as delta waves. In contrast during REM sleep, the brain is almost as active as when awake. We experience robust dreams during REM sleep with lots of neuron activity, which can be detected as the more frequent theta waves that are also seen in relaxed awake brains.

Despite its low brain activity, deep sleep is thought to be where memories are consolidated for long-term storage. Disrupting deep sleep in rodents impacts their memory recall, while the same is not true when disrupting REM sleep. Yet with such low brain activity, it's unclear how deep sleep allows for memory formation.

One major challenge of measuring brain electrical waves in people is the strength of the signal. The electrodes are placed on the patient’s head, meaning the signal they receive is predominantly from the outermost layer of the brain known as the cortex. For most cases this is great data to have! The cortex is responsible for many of our complex functions, like abstract reasoning, problem solving, and memory recall. So measuring its activity is a great resource.

Yet during deep sleep, cortex functions are diminished. The cortical neurons are pretty tired and want to rest, resulting in the infrequent delta wave electrical signals. But hidden beneath them in the depths of our brains is a slurry of activity during deep sleep.

Scientists in Chongqing, China, found this activity by giving mice a test: a maze. The mice attempted to solve the maze during the day. The researchers implanted electrodes deep in their brains to see which neurons were activating as they found the correct path through. And at night, they measured these same neurons to see at what stage of sleep they “remembered” the maze path.

And what they found was that during deep sleep, neurons deep in the brain exhibited theta wave activity typically seen during REM sleep. The brain was very much still active. But it was deep in the brain near the hippocampus. So deep that its activity cannot reach external electrodes normally used to measure human sleeping patients.1 But in this animal study the researchers implicated the electrodes deep in their brain, picking apart this subtle activity.

And indeed this activity appeared to be the brain returning to the maze pathway, and storing it in memory. When the researchers disrupted this deep cycle of sleep, the mice had trouble with the maze the next day. When the mice had proper deep sleep, the maze was easy for them.

We already knew the hippocampal region of the brain is essential to memory formation. But its activity during deep sleep was so far a mystery. Indeed during the deepest part of our sleep, when the rest of our brain is very quiet, the hippocampus is hard at work storing those memories.

But how does our brain store this information as memories?

While awake and when doing pretty much anything, billions of our neurons are actively communicating with one another. These neurons, through their minute electrical signals, are responsible for controlling interactions with our environments (like moving our limbs) while simultaneously recording and processing the information we see. That’s no small order. It’s enough electrical activity to use about 12 watts of power.

Yet we need to remember many, many, many things. And like a computer harddrive, there is only so much information our brains can store. So our neurons need to figure out which parts of our interactions are important, and encode that in their synapses. Ideally using as few synapses as possible.

And again, let’s return to the hippocampus. We have already mentioned that the hippocampus has established itself as essential to memory formation, and that its activity is present during deep sleep cycles. It probably has some role in distilling our experiences into neatly packaged memories, too.

New research from Drexel University elucidates this memory storage process. When exposing mice to cages where the floors had patterns of shock-wires, the trauma creates predictable memory formation. Electrodes implanted in the mice’s hippocampus measured how these neurons activated in response to the shocking floor, and how these neurons reactivated during deep sleep and the following day. The memory of the electrically-charged floor robustly stimulated the brain, leading to many millions of neurons activating.

In the hippocampus, there are two distinct types of neurons: dCA1, and BLA. During deep sleep many dCA1 neurons are activated, and they communicate with a tiny subset of BLA neurons. And then the following day when the mice are back in the shock cages, those few BLA neurons fire and activate a large swath of dCA1 neurons. In other words: the millions of neurons that activate in response to environmental factors are downsampled to a few BLA neurons, encoding that information. To regenerate the memory, those handful of BLA neurons activate, which regenerates the same memory by activating the same neurons as when the memory occurred in the first place. This encoder-decoder architecture is mediated by dCA1 neurons.

This is very similar to many-to-one mapping in data storage and retrieval systems. Or to the encoder-decoder architecture present in many artificial intelligence systems. The authors mention how powerful this system is in our brains:

[I]t provides robustness and redundancy, thereby enhancing single-trial learning and minimizing potential disruptions from background or external noises. It is noteworthy that single-trial learning and memory formation are recognized as features of biological intelligence in comparison to long-training sessions of artificial intelligence.

In contrast to artificial intelligence systems, which take many training iterations and data points to learn patterns, our brains can form memories from a single experience. Understanding how our brains are able to prioritize what to remember and encode from just a single data point is key to expanding artificial intelligence's capabilities. As we talked about last time, reverse engineering biological intelligence is key to upgrading artificial intelligence. And the answer may be hiding in our unconscious brainwaves.

Sleeping outside the brain

The benefits of sleep go beyond our brain. Far beyond it, in fact. Two additional papers point to how sleeping helps us recover from heart attacks and how it regulates our metabolism.

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the US and many high-income countries around the world. One of the most prominent indications of heart disease is a heart attack. Needless to say, heart attacks are quite detrimental to our health. They can directly lead to heart failure, or to lifelong heart diseases like arrhythmias.

A well-established connection between immune cells and heart cells is essential to recovering from heart attacks. How the immune cells in our heart behave following a heart attack is integral to our body’s recovery. If the inflammation is too intense, this recovery is impaired and the patient is at risk for heart failure. But if there is too little inflammation, the immune cells cannot clear out dead cells and subsequent heart attacks are more likely.

Sleep is also important to heart attack recovery. While we sleep, our cells utilize the energy that our sleeping brains don’t need to divide more frequently, repairing damaged tissues. And indeed sleep disruption makes patients more likely to suffer from future heart attacks. Getting plenty of rest is key to recovery.

Scientists and doctors at the Icahn School of Medicine in New York have found that immune cells stimulate our brain to sleep more after heart attacks. The same cells that help clear up the diseased heart tissue (monocytes) also travel to the brain and produce signaling proteins known as cytokines. These proteins induce our brains to sleep by activating glutamatergic neurons, who signal to the rest of the brain to sleep deeper and for longer.

And in turn, that sleep induction actually reduces inflammation in the heart. So the ideal workflow is: 1) Heart attack induces an immune response, which cleans up the diseased heart tissue, 2) Our brain recruits immune cells, who produce signaling proteins to induce sleep 3) The excess sleep helps tamp down inflammation, allowing the cleaned up heart tissue to recover.

During animal experiments in mice, when the mice had their sleep disrupted after a heart attack, the immune cell inflammation in the hearts persisted much longer. And their recovery was diminished when compared to mice that slept fully.

The authors discuss this heart-brain-immune axis and its importance in our lives:

The immune, cardiac, and nervous systems are deeply interconnected and together coordinate brain–heart circuits to influence behavioural and inflammatory outcomes during cardiovascular disease.

[Heart attack] induces a massive and consequential immune response. Although much focus has rightly been on immune outcomes in the heart and medullary organs post-[heart attack], little has been known about immune changes in remote non-injured tissues.

[N]euroinflammation post-[heart attack] is a beneficial and protective response that increases sleep to restrain cardioinflammation.

This newfound axis where the brain, heart, and immune cells all act in tandem is a novel approach to understanding our body’s recovery process. To what extent this applies to other injuries and diseases is an open question. But the author’s point to sleep’s lack of prioritization in medical advice:

Cardiac rehabilitation counselling focuses on appropriate lifestyle modifications after [acute coronary syndrome] to improve heart healing and health. Yet, many of these programmes do not incorporate sleep. Our study supports sleep as having a major influence on cardiac outcomes that mitigate health deterioration after an acute cardiac event. Healthful sleep should therefore be incorporated into post-[heart attack] clinical management.

Sleep is essential to recovery from diseases, particularly heart attacks. So much so that our body induces extra sleep after a heart attack. Listen to your body! This extra sleep can save your life.

We (or atleast I) tend to think of sleep as a brain-thing. Our brains go to sleep to let the rest of our bodies take advantage of that extra energy. Fundamentally, it's our neurons who regulate our circadian rhythm and induce sleep.

But sleep isn’t quite that black-and-white. As we just saw, immune cells can signal to our brain to produce melatonin and sleep deeper following injury. The brain does ultimately control the production of melatonin and other neurotransmitters for sleeping, but they can be heavily influenced by external agents like immune cells.

Additionally the circadian rhythm, our biological clock, is not isolated to neurons. Our individual cells can and do keep track of time outside of our nervous system. Individual cells, including bacteria and plant cells, have their own biological clocks to keep track of days or even of the seasons. This time-keeping mechanism is essential to their survival in harsh environments.

(For an excellent writeup on the molecular biological clock in these cells, check out the Asimov Press essay here).

Another organ system that relies on circadian rhythm is our digestive tract. Our metabolism is tightly controlled throughout the day-night cycle. As mentioned above, a 5-hour disruption in the sleep cycle impacts metabolism temporarily. For night-shift workers, this disruption can lead to metabolic disorders.

For the sake of these workers and for the general public, we want to know why. Why does sleep disruption cause metabolic disease? What is the mechanism there?

And in fact we again return to immune cells! There are a special class of immune cells that produce a particular signaling protein called IL17. And these IL17-producing immune cells are enriched in our digestive tract and fat tissue. Previous research has shown that these immune cells are really important for fat metabolism: they help digestive cells break down fat in foods, and to generate fat tissue for temperature regulation.

What scientists at Trinity College Dublin in Ireland found was that these IL17-producing immune cells also produced many of the genes involved in the circadian rhythm. The immune cells kept track of time on their own! And they used this time signature to signal to our body whether to break down fat or to build more fat in the day or night, respectively.

The immune cell’s production of IL17 followed this clock. At night, when mice are feeding, IL17 production is highest and the cells convert their food into fats for energy storage. Then during the day, IL17 production is much lower.2 The mice break down their fats into carbohydrates for energy.

This regulation of immune cell activity is complementary but separated from the sleep rhythm of our brains. And it's essential to our metabolic health. When this cycle was disrupted, such as by inhibiting the activity of IL17, the mice became susceptible to hypothermia and autoimmune diseases.

It’s clear that sleep has an integral role to our health. It gives our cells a chance to rest and recover. But more than that, many of our natural processes happen cyclically. We rely on the circadian rhythm to maintain our metabolism and our immunity. And this is even more true when we are sick or recovering from an illness, especially one as severe as a heart attack. Sleep truly is the best medicine.

This is because the signal intensity of electroencephalogram data from external electrodes is inversely proportion to the square of the signal's depth in the brain.

Mice follow a different sleeping and eating schedule than we do, eating around midnight and then fasting during the day. In humans, this cycle is flipped. Although the study of IL17 production throughout the day-night cycle is a topic of active study, we typically eat only during the day and fast during the night, while sleeping. So IL17 production in humans is expected (from my interpretation) to follow an inverse schedule from mice: peaking during the day to breakdown food into fats, then leveling off during the night to breakdown fats into energy.